The western honey bee – Apis mellifera – is today found throughout the world, having been taken with settlers to every continent except Antarctica! However they are originally native to Europe and west Asia. Like many other animals honey bees are actually made up of a number of subspecies, evolved to best survive in different regions, each with their own challenges.

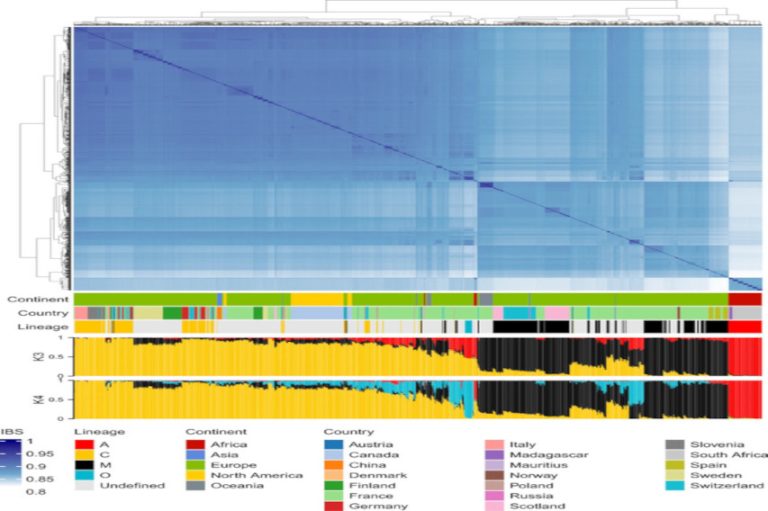

There are over 30 subspecies of honey bee, with more continuing to be identified as genetic testing allows for more detailed analysis. We have a good idea of the historical range of each subspecies from historical records and museum collections, but since the 1800s beekeepers have been moving colonies around between different countries, introducing subspecies into areas where they weren’t previously found, and leading to hybridisation between subspecies and ‘blurring of the lines’ as to which bees are found in which areas.

As can be seen on the map, the native subspecies of north-western Europe, including the UK, is Apis mellifera mellifera – often referred to as the black bee or European dark bee. This bee has a wide-range of adaptations for a northern climate, including smaller, more frugal colonies, foraging at lower temperatures, and a preference for supersedure instead of swarming.

The 2 other subspecies commonly found in the UK are Apis mellifera carnica – or Carniolan bee – and Apis mellifera ligustica – or Italian bee. These bees have been imported into the UK from eastern and southern Europe since the 1800s, and high numbers of imports continue to the present day. These subspecies often produce larger colonies, producing more honey (when the weather is suitable!) and are commonly used in commercial beekeeping as a result. However they are less well adapted to the UK’s climate, and may require more beekeeper management to survive, such as extra feeding.

Unlike other animals used by man, controlling honey bee mating is much more difficult, since it takes place on the wing, away from the hive. As a result colonies will readily hybridise, leading to new generations that carry some of the traits of each of the parents. This hybridisation can sometimes be an advantage for beekeepers, leading to ‘hybrid vigour’ and very strong productive colonies, but it can also lead to dilution of the native genetics by the introduction of genes that lead to bees less able to survive in a northern climate.

Due to a combination of disease and importation, it was long believed that the native bee had been more or less replaced entirely by hybrids with the other introduced subspecies. However when looking at physical characteristics, pockets of apparently dark native bees continued to persist in more remote areas, such as the Scotland, Wales and Cornwall. Additionally, despite the high levels of annual imports, British bees still appeared to show signs of hybridisation, implying that the native genetics were still present in the population.

With the advent of genetic testing, it was possible to identify pure native bees from protected areas, such as those on Colonsay, and then compare their genetics to those elsewhere in the UK. This research (by our own Dr Mark Barnett) found that the level of native genetics was still surprisingly high across the UK, not just in remote areas, and this has spurred on conservation groups to investigate what can be done to try to preserve the native bee and encourage it’s growth. It is believed that the suitability of dark bee genees for our environment is what allows them to ‘win out’ and stay present in the population, even with the introduction of other subspecies.

It is on the back of this growth in interest in the native honey bee, and honey bee genetics more widely, that Beebytes was formed. We offer genetic testing services and consultancy for those who are interested in all aspects of honey bees, but with a special focus on environmental and conservation projects. Ultimately we hope to be able to improve the health and survival of honey bees and other pollinators through our work, for the benefit of insects, people and the planet.